The only relevant behaviours by members of a group of participants are those which are compatible with one another. Behaviours that are not compatible with the behaviours of others (e.g., with competitors and with the other side of the market) are not sustainable, regardless of the intentions of any one individual. Most people are familiar with this idea, in the sense of having heard the phrase “at the equilibrium price, quantity supplied equals quantity demanded”. Economists make a good living reminding people of this idea because too many people think “Supply and Demand. Boringly Obvious!”. In this post, I want to convince you that the idea is not obvious and that it is certainly not boring.

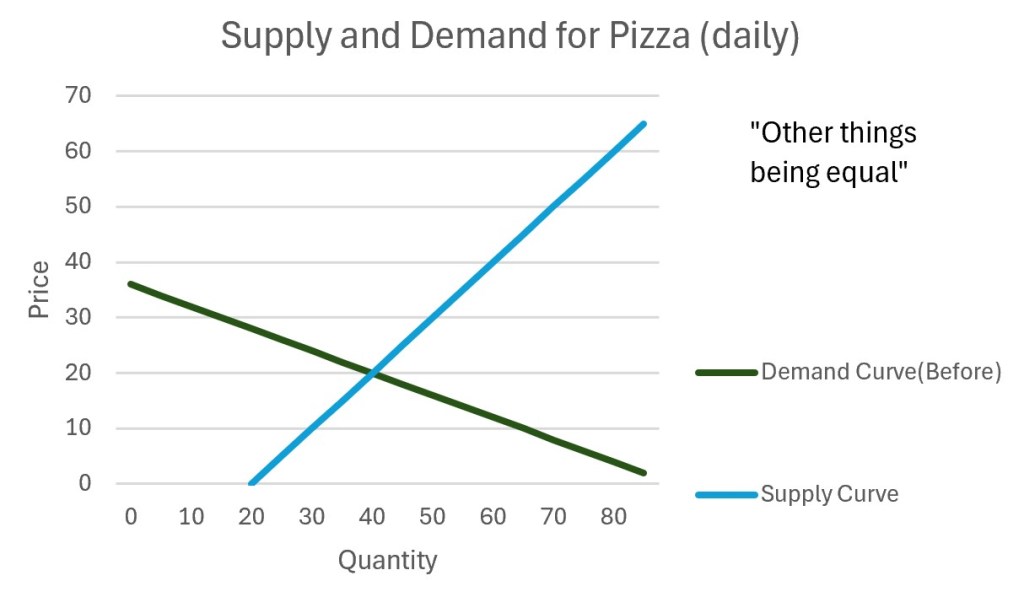

This graph shows what most people associated with economics: there are buyers and sellers and, somehow, there is an equilibrium price and quantity. Economics classes spend a lot of time discussing different types of equilibrium: e.g., “perfectly competitive equilibrium” (both “short run” and “long run”), “Nash Equilibrium”, and “monopolistic competitive equilibrium”. Each of these bits of jargon embodies the idea of compatibility to show why, out of the many possible outcomes, few are relevant.

Even a monopolist must act in a way that is compatible with the actions of buyers as a whole. Buyers must still agree to open their wallet and buy as much as the firm wants to sell at the price chosen by the monopolist. A business would be more successful if consumers acted in the best interest of the company. It is also true that the consumer’s life could be better if companies acted in their best interest or if the government gave each person $100,000 just because. Reality shows that the interests (or tastes or preferences or …) of buyers are independent of the goals (or objectives or priorities or …) of businesses. So, a realistic analysis of any market situation requires understanding how the actions of everybody fit together: i.e., if they are compatible.

Life experience vs. Understanding

Many people have experience or expertise on one side of a market, for example as a consumer buying groceries or as somebody looking for a job. That experience informs their advice on how life could be made better for consumers or job seekers. Some of that advice ignores the motives and constraints that employers live with: e.g., few employers can afford to lower the price to everybody or to hire everybody who applies for a job. Similarly, consumers are happy when a salesperson gives them a special deal “because you are a nice person”. And they complain when that price rises “just because”. They could benefit from understanding why the price rises or falls. Individual experience differs from the experience of a group of individuals.

This blind spot afflicts experts on the seller side also. A student of business may be an expert on their firm, and be able to describe the nuances of production technology which increase their production. This expertise does not help them to anticipate what would happen if their firm and all of the competitors increase production at the same time: e.g., what would happen if there were excess supply. These students of business are not thinking deeply about how their business fits into the rest of an economy. This change in perspective is uncomfortable to many business students. In my opinion, the widespread failure to recognize the shift in perspective from an individual to a large group is why students of business should be required to study economics formally.

Some non-economists talk about the “chaos of the market” where, it seems, nothing is predictable and, certainly, it seems to be silly to talk about a well-defined equilibrium. In many cases, that kind of talk reveals that the person does not know what to focus on. They can be easily distracted by shiny objects, boutique government policies and administrivia. One of the hidden lessons of the equilibrium principle, and the formality of economic models, is that it gives an idea of what is worth focusing on.

A deeper lesson of the equilibrium principle is that it distinguishes two types of variables: endogenous variables which are characterized by the compatibility and exogenous variables which are treated as data for which no attempt is made to explain. The most familiar endogenous variables are the market price and the total quantity demanded: they adapt to conditions set by forces outside of a market. Exogenous variables define the context of the problem which a market must “solve”. The list of variables exogenous to a market is much longer. On the demand side, the list includes consumer income (and its distribution), population, consumer tastes (and its distribution), and related variables. On the supply side, the list includes production technology, input prices (wages, costs of capital, …), goals of firms, and related variables.

A Hint when Writing a Test and when Reading “Up and Down Economics”

So, as a hint to students preparing for a test, pay close attention whenever an instructor distinguishes a “movement along a curve” and “a shift of a curve”. The two changes look alike in a one-dimensional sense: the change in quantity. They can be distinguished if you focus on changes in both quantity and price. On a supply and demand graph such as that shown above,

- “movement along a curve”: a change in quantity due to a change in price; often the result of a shift in the other curve

- “a shift of a curve”: a change in quantity without a change in price; often causes a movement along the other curve.

Because it is also a source of unexpected insights, this distinction is commonly found in tests. Later, when the answers are being reviewed, the instructor can say “You should have recognized the distinction: as I said in class, not every change in quantity has the same meaning”.

The same ideas apply when reading an analysis written in plain language. Up and down economics uses formal logic less often, which means that the author may be confused about the difference between cause and effect and may mislead the reader.

The Meanings embedded in a “Supply and Demand” Graph

A demand curve shows what is intuitively obvious to buyers: e.g., if the price falls then they want to buy more and if income increases they want to buy more. A supply curve shows what is intuitively obvious to sellers: e.g., if the price rises then they want to increase production and if the costs of production increases then sellers want to reduce production. The difference in motives between buyers and sellers concerning price is robust, seemingly-irreconcilable and seems to justify the perception of “chaos of the market”. The insight of the equilibrium principle, emphasized by the point where the supply curve and the demand curve intersect on a graph, is that the actions of buyers and of sellers are compatible at that point. At that point, you do not need to choose whether the buyer intuition dominates the seller intuition or the reverse: both apply. When normally incompatible motives lead to actions which are compatible, it is worth paying attention.

Once the equilibrium principle is understood, the discussion can change to: what would change the price or quantity? The answer to that question depends on understanding changes in exogenous variables.

Now, it is your time to write

- Many commentators offer examples where (in effect) a firm tells consumers what to buy and how much, often using market share as evidence of market power. Even if true, this evidence may be incomplete. Critical thinking often benefits from asking: are there any counter-examples? The example of New Coke [1] [2] is well-studied but may be too old now. So, can you think of any more recent counter-examples where a supposedly powerful company told consumers what to buy and consumers said “meh”? What does comparing examples and counter-examples reveal to you?

Leave a reply to Improving your Financial Literacy: Fear, Greed and Investing – 5 Basic Principles of Economics Cancel reply